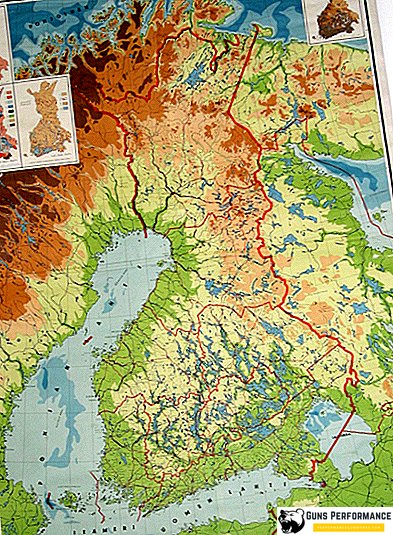

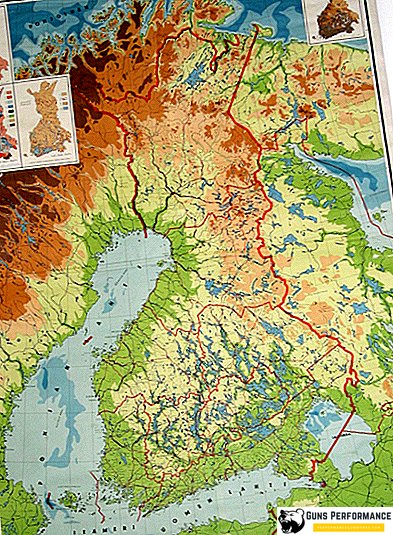

After the Civil War of 1918–1922, the USSR received quite unfortunate and poorly adapted borders. So, the fact that the Ukrainians and Belarusians were divided by the state border line between the Soviet Union and Poland was completely ignored. Another such "inconvenience" was the proximity of the border with Finland to the northern capital of the country - Leningrad.

In the course of the events preceding the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union received a number of territories, which made it possible to significantly move the border to the west. In the north, this attempt to move the border encountered some resistance, called the Soviet-Finnish, or Winter, war.

Historical background and origins of the conflict

Finland as a state appeared relatively recently - on December 6, 1917, against the backdrop of a collapsing Russian state. At the same time, the state received all the territories of the Grand Duchy of Finland together with Petsamo (Pechenga), Sortavala and the territories on the Karelian Isthmus. Relations with the southern neighbor also went wrong from the very beginning: in Finland, a civil war died down, in which the anti-communist forces triumphed, so there was clearly no sympathy for the USSR, which supported the Reds.

However, in the second half of the 20s - the first half of the 30s, relations between the Soviet Union and Finland stabilized, being not friendly, but not hostile either. Defense spending in Finland declined steadily in the 20s, peaking in 1930. However, the arrival of the post of War Minister Carl Gustav Mannerheim somewhat changed the situation. Mannerheim immediately set about rearming the Finnish army and preparing it for possible battles with the Soviet Union. The fortification line was originally inspected, at that time the name of the Enkel line. The state of its fortifications was unsatisfactory, so the re-equipment of the line began, as well as the construction of new defensive lines.

At the same time, the Finnish government has taken vigorous steps in order to avoid conflict with the USSR. In 1932, a non-aggression pact was concluded, the term of which was to be completed in 1945.

Events of 1938-1939 and causes of conflict

By the second half of the 1930s, the situation in Europe was gradually heating up. The anti-Soviet statements of Hitler forced the Soviet leadership to look more closely at the neighboring countries, which could become allies of Germany in a possible war with the USSR. The position of Finland, of course, did not make it a strategically important bridgehead, since the local nature of the terrain inevitably turned the fighting into a series of small battles, not to mention the impossibility of supplying huge masses of troops. However, the close position of Finland to Leningrad could still turn it into an important ally.

It was these factors that forced the Soviet government in April-August 1938 to begin negotiations with Finland regarding guarantees of its non-alignment with the anti-Soviet bloc. However, in addition, the Soviet leadership also demanded the provision of a number of islands of the Gulf of Finland under the Soviet military bases, which was unacceptable for the then Finnish government. As a result, the negotiations ended in vain.

In March-April 1939, new Soviet-Finnish negotiations took place, during which the Soviet leadership demanded the lease of a number of islands in the Gulf of Finland. The Finnish government also was forced to reject these demands, as it was afraid of "Sovietization" of the country.

The situation began to glow rapidly when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed on August 23, 1939, in a secret supplement to which it was indicated that Finland was within the scope of the interests of the USSR. However, even though the Finnish government did not have data on a secret protocol, this agreement made him think seriously about the future prospects of the country and relations with Germany and the Soviet Union.

Already in October 1939, the Soviet government put forward new proposals for Finland. They envisaged the movement of the Soviet-Finnish border on the Karelian Isthmus 90 km to the north. In exchange, Finland should have received approximately twice the territory in Karelia, in order to significantly secure Leningrad. A number of historians have also expressed the opinion that the Soviet leadership was interested in, if not sovietizing Finland in 1939, then at least depriving it of protection in the form of a fortification line on the Karelian Isthmus, already then called the Mannerheim Line. This version is very consistent, as further events, as well as the development of a plan for a new war against Finland by the Soviet General Staff in 1940, indirectly indicate this. Thus, the defense of Leningrad, most likely, was only a pretext for turning Finland into a convenient Soviet bridgehead, such as, for example, the Baltic countries.

However, the Finnish leadership rejected the Soviet demands and began to prepare for war. Preparing for war and the Soviet Union. In total, by the middle of November 1939, 4 armies were deployed against Finland, comprising 24 divisions with a total of 425,000 men, 2,300 tanks and 2,500 aircraft. Finland had only 14 divisions totaling approximately 270 thousand people, 30 tanks and 270 airplanes.

In order to avoid provocations, the Finnish army in the second half of November received an order to withdraw from the state border on the Karelian Isthmus. However, on November 26, 1939, an incident occurred, the responsibility for which both parties put on each other. Soviet territory was shelled, with the result that several soldiers were killed and wounded. This incident occurred in the area of the village of Minela, from which it got its name. Clouds thickened between the USSR and Finland. Two days later, on November 28, the Soviet Union denounced the non-aggression pact with Finland, and two days later the Soviet troops received an order to cross the border.

The beginning of the war (November 1939 - January 1940)

November 30, 1939, Soviet troops launched an offensive in several directions. At the same time, hostilities immediately took on a fierce character.

On the Karelian Isthmus, where the 7th Army was attacking, the Soviet troops managed to capture the city of Terijoki (now Zelenogorsk) on December 1, at great cost. Here it was announced the creation of the Finnish Democratic Republic, headed by Otto Kuusinen, a prominent figure in the Comintern. It was with this, the new "government" of Finland, that the Soviet Union established diplomatic relations. At the same time, in the first decade of December, the 7th Army was able to quickly seize the assumption, and rested against the first echelon of the Mannerheim line. Here the Soviet troops suffered heavy losses, and their advancement almost stopped for a long time.

North of Lake Ladoga, in the direction of Sortavala, the 8th Soviet Army was advancing. As a result of the first days of fighting, she managed to move 80 kilometers in a relatively short time. However, the Finnish troops who opposed it, managed to carry out a lightning operation, the purpose of which was to surround part of the Soviet forces. The Finns played into the hands of the fact that the Red Army was very strongly tied to the roads, which allowed the Finnish troops to quickly cut its communications. As a result, the 8th Army, having suffered serious losses, was forced to retreat, but until the end of the war it retained part of Finnish territory.

The least successful were the actions of the Red Army in central Karelia, where the 9th Army was advancing. The task of the army was to conduct an offensive in the direction of the city of Oulu, with the aim of "cutting" Finland in half and thereby disorganizing the Finnish troops in the north of the country. On December 7, the forces of the 163rd Infantry Division occupied a small Finnish village Suomussalmi. However, Finnish troops, having superiority in mobility and knowledge of the terrain, immediately surrounded the division. As a result, the Soviet troops were forced to occupy all-round defense and repel the sudden attacks of the Finnish skiing units, as well as incur substantial losses from sniper fire. The 44th Rifle Division, which soon also became surrounded, was launched to the aid of the encircled.

Assessing the situation, the command of the 163rd Infantry Division decided to make its way back. At the same time, the division suffered losses of approximately 30% of the personnel, and also abandoned almost all equipment. After its breakthrough, the Finns managed to destroy the 44th rifle division and practically restore the state border in this direction, paralyzing the actions of the Red Army here. The result of this battle, called the Battle of Suomussalmi, were rich trophies taken by the Finnish army, as well as an increase in the overall morale of the Finnish army. At the same time, the leadership of two divisions of the Red Army was subjected to repression.

And if the actions of the 9th Army were unsuccessful, then the forces of the 14th Soviet Army, advancing on the Rybachi Peninsula, were most successful. They managed to capture the city of Petsamo (Pechenga) and large nickel deposits in the area, as well as reach the Norwegian border. Thus, Finland at the time of the war lost access to the Barents Sea.

In January 1940, the drama broke out and south of Suomussalmi, where the scenario of the recent battle was repeated in general terms. The 54th Infantry Division of the Red Army was surrounded here. At the same time, the Finns did not have enough strength to destroy it, so the division was surrounded by the end of the war. A similar fate awaited the 168th rifle division, which was surrounded in the area of Sortavala. Another division and a tank brigade were encircled in the Lemetti-Yuzhny area and, after suffering huge losses and losing almost all of the materiel, they still made their way out of the encirclement.

By the end of December, fighting on the breakthrough of the Finnish fortified line on the Karelian Isthmus subsided. This was explained by the fact that the Red Army command was well aware of the futility of continuing further attempts to attack the Finnish troops, which only caused serious losses with minimal results. The Finnish command, realizing the essence of the lull at the front, launched a series of attacks in order to thwart the Soviet offensive. However, these attempts were failed with great losses for the Finnish troops.

However, the overall situation remained not very favorable for the Red Army. Her troops were involved in battles on foreign and poorly studied territory, in addition in adverse weather conditions. The Finns did not have superiority in numbers and technology, but they had a streamlined and well-developed tactic of guerrilla warfare, which allowed them, acting with relatively small forces, to inflict significant losses on the advancing Soviet troops.

February offensive of the Red Army and end of the war (February-March 1940)

February 1, 1940 on the Karelian Isthmus began a powerful Soviet artillery preparation, which lasted 10 days. The task of this training was to inflict maximum damage on the Mannerheim Line and Finnish troops and wear them down. On February 11, the troops of the 7th and 13th armies moved forward.

Across the front, fierce battles took place on the Karelian Isthmus. The main blow Soviet troops inflicted on the town of Summa, which was located on the Vyborg direction. However, here, as well as two months ago, the Red Army again began to tie up in battles, so soon the direction of the main attack was changed, on Lyakhda. Here the Finnish troops could not hold back the Red Army, and their defense was broken through, and a few days later the front page of the Mannerheim Line. The Finnish command was forced to begin withdrawing troops.

February 21, Soviet troops reached the second line of the Finnish defense. Here fierce battles again unfolded, which, however, by the end of the month ended with a breakthrough of the Mannerheim Line in several places. Thus, the Finnish defense collapsed.

In early March 1940, the Finnish army was in a critical situation. The Mannerheim Line was broken, the reserves were almost depleted, while the Red Army was developing a successful offensive and had almost inexhaustible reserves. The morale of the Soviet troops was also high. Earlier this month, the troops of the 7th Army rushed to Vyborg, the battles for which continued until the cease-fire on March 13, 1940. This city was one of the largest in Finland, and its loss could be very painful for the country. In addition, in this way, Soviet troops opened the way to Helsinki, which threatened Finland with a loss of independence.

Taking into account all these factors, the Finnish government set a course to start peace talks with the Soviet Union. March 7, 1940 peace negotiations began in Moscow. As a result, it was decided to cease fire from 12 noon on March 13, 1940. The territory on the Karelian Isthmus and in Lapland (the cities of Vyborg, Sortavala and Salla) departed to the USSR, and the Hanko peninsula was also leased.

Results of the Winter War

Estimates of Soviet losses in the Soviet-Finnish war vary considerably, and according to the data of the Soviet Ministry of Defense, about 87,500 people are dead and dead from wounds and frostbite, as well as about 40,000 missing. 160 thousand people were injured. The losses of Finland were significantly smaller - about 26 thousand dead and 40 thousand wounded.

As a result of the war with Finland, the Soviet Union was able to ensure the security of Leningrad, as well as strengthen its position in the Baltic. This primarily concerns the city of Vyborg and the Hanko Peninsula, on which Soviet troops began to be based. At the same time, the Red Army received combat experience in breaking through the fortified line of the enemy in severe weather conditions (the air temperature in February 1940 reached -40 degrees), which no army of the world had at that time.

However, at the same time, the USSR received in the north-west, albeit not a powerful, but an enemy, who already in 1941 had let German troops into its territory and contributed to the blockade of Leningrad. As a result of Finland’s performance in June 1941 on the side of the Axis countries, the Soviet Union gained an additional front with a sufficiently large length, diverting from 20 to 50 Soviet divisions from 1941 to 1944.

Britain and France also closely followed the conflict and even had plans to attack the USSR and its Caucasian fields. At present, there are no complete data on the seriousness of these intentions, but it is likely that in the spring of 1940 the Soviet Union could simply “quarrel” with its future allies and even be drawn into military conflict with them.

There are also a number of versions that the war in Finland indirectly influenced the German attack on the USSR on June 22, 1941. Soviet troops broke through the Mannerheim Line and practically left Finland in March 1940 defenseless. Any new invasion of the Red Army in the country could well be fatal for it. After the defeat of Finland, the Soviet Union would approach a dangerously short distance to the Swedish mines in Kiruna, one of the few sources of metal for Germany. Such a scenario would put the Third Reich on the brink of disaster.

Finally, the not very successful offensive of the Red Army in December-January strengthened in Germany the belief that Soviet troops were essentially ineffective and did not have good commanders. This misconception continued to grow and reached its peak in June 1941, when the Wehrmacht attacked the USSR.

As a conclusion, we can point out that as a result of the Winter War, the Soviet Union still acquired more problems than victories, which was confirmed in the next few years.